In her latest book, UCLA’s Kara Cooney notes how a ruler’s gender matters far less than whose agendas are served

Over the course of 3,000 years of Egypt’s history, six women ascended to become female kings of the fertile land and sit atop its authoritarian power structure. Several ruled only briefly, and only as the last option in their respective failing family line. Nearly all of them achieved power under the auspices of attempting to protect the throne for the next male in line. Their tenures prevented civil wars among the widely interbred families of social elites. They inherited famines and economic disasters. With the exception of Cleopatra, most remain a mystery to the world at large, their names unpronounceable, their personal thoughts and inner lives unrecorded, their deeds and images often erased by the male kings that followed, especially if the women were successful.

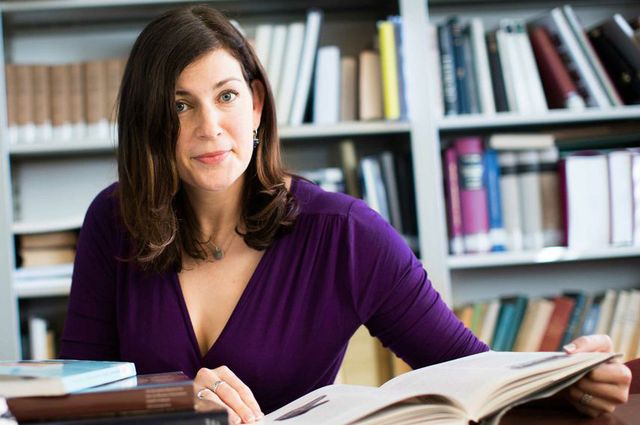

In her latest National Geographic book, “When Women Ruled the World” Kara Cooney, professor of Egyptian art and architecture and chair of the UCLA Department of Near East Languages and Cultures tells the stories of these six women: Merneith (some time between 3000–2890 B.C.), Neferusobek (1777–1773 B.C.), Hatshepsut (1473–1458 B.C.), Nefertiti (1338–1336 B.C.), Tawroset (1188–1186 B.C.) and Cleopatra (51–30 B.C.).